How AI-driven feedback loops could make things very crazy, very fast

A primer

When people picture artificial general intelligence (AGI), I think they often imagine an even smarter version of ChatGPT. But that’s not where we’re headed.

The frontier AI companies are trying to build a fully fledged “digital worker” which can go and complete open-ended tasks like building a company, overseeing scientific experiments, or controlling military hardware. If they succeed, it would create totally different dynamics to existing LLMs, and have much wilder consequences.

The reason is the effect of feedback loops that could accelerate the pace of change by ten or even one hundred times.

The feedback loop that’s received the most attention in the past is the one in algorithmic progress. If AI could learn to improve itself, the argument goes, maybe it could start a singularity that leads rapidly to superintelligence?

But there are other feedback loops that could still make things very crazy – even without superintelligence – it’s just that they take five to twenty years rather than a few months. The case for an acceleration is more robust than most people realise.

This article will outline three ways a true AI worker could transform the world, and the three feedback loops that produce these transformations, summarising research from the last five years.

While the first concern most people have about AGI is mass unemployment, things could get a lot weirder than that, even before mass unemployment becomes possible.

Throughout, I don’t try to assess whether or when this sort of digital worker will be ready to deploy, but rather assume it will be, and explore what happens next.

1. The intelligence explosion

Algorithmic feedback loops

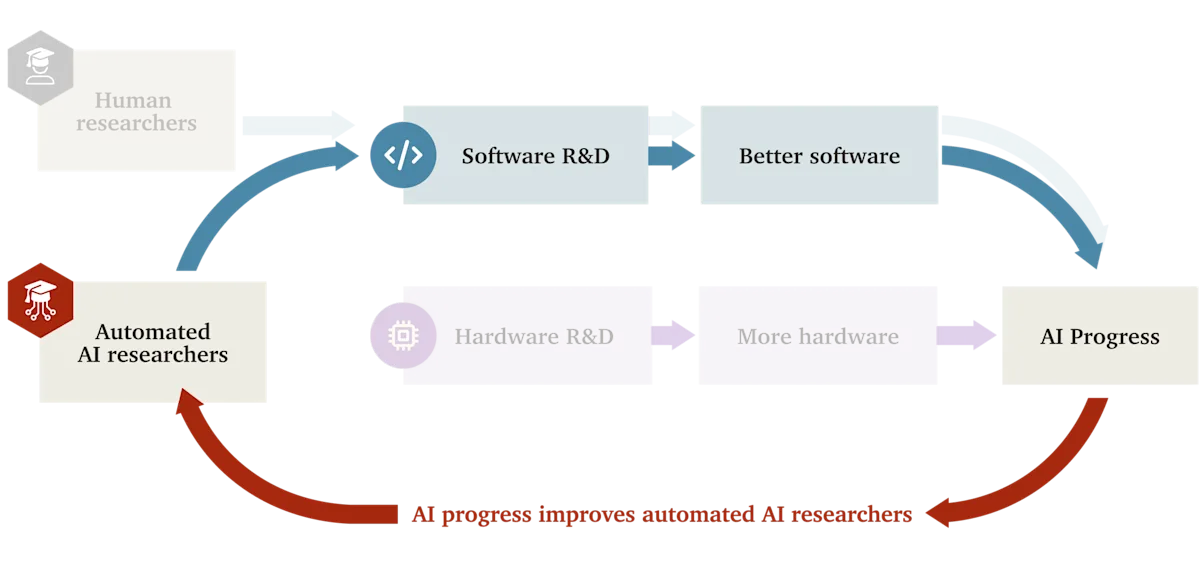

In the 1960s, Alan Turing and I. J. Good saw that if AI began to help with AI research itself, then progress in AI research would speed up, which would lead to AI becoming even more advanced, perhaps producing a ‘singularity’ in intelligence.1 Back then this was a purely theoretical argument, but in the last five years we’ve gained much more empirical grounding for how this (and other) feedback loops could work.

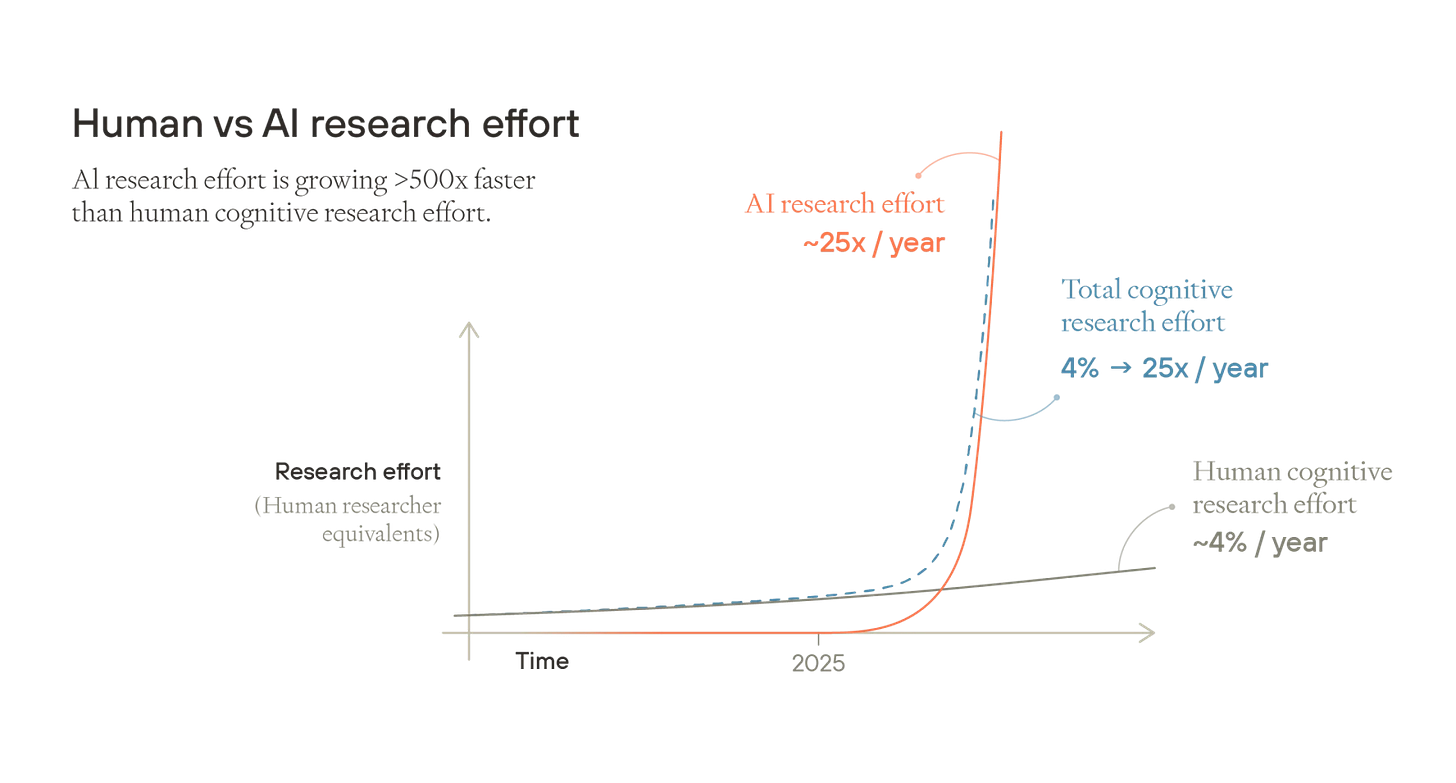

The leading AI companies today already use AI extensively to aid their own research, especially to help with coding training, tests, and experiment scaffolding.2 So far, the overall boost to the productivity of these researchers seems still relatively small, perhaps 3-30%.3 But as AI tools improve, the boost to their productivity will increase.

Now imagine that the process continues, and the models keep getting better. Eventually, they become able to do the job of a junior engineer, and then a mid-level engineer, and continue to improve from there.4

If current models could produce work comparable to that of a mid-level engineer, then given the amount of computing power already available in datacentres today, it would be possible to produce output equivalent of millions of competent engineers working on AI research.5 There’s probably under 10,000 human researchers working on frontier AI today, so each human researcher working on AI today would have the equivalent of 100 assistants.

As AI continues to improve, eventually these models in turn could start to do the work of even top researchers, with minimal human direction.

No-one knows exactly how much that would speed up progress, but much comes down to a single question:

If you double the amount of research effort going into AI algorithms (holding the number of chips constant), do the algorithms at least double in quality?

If yes, then each time the number of digital AI researchers doubles, that unlocks advances that allow you to run AIs that are twice as effective, which then allows the population of digital researchers to double again, and so on, until you approach some other limit.

There have been empirical estimates which quantify the returns of past algorithmic research, which find that while the value could be below 1, there’s a good chance it’s above, which would start a positive feedback loop.

The next question is how quickly the feedback loop fizzles out as it runs into other constraints. The most complete model of both effects I’ve seen is by Tom Davidson, who currently works at Forethought, an Oxford-based research institute founded to study the impact of AI. In March 2025, Tom estimated we’d most likely get three years of AI progress in one year, and it’s possible we’d see ten.6

What would three years of progress in one year look like? Over the last five years, the number of AI models you can run on a given number of computer chips has increased over three times per year as algorithms have become more efficient.7 That means if you start with 10 million digital workers, three years of progress in one year means that one year later you could run about 270 million of them.

These models would also be smarter. Three years of progress is more than the gap between the original GPT-4, which sucked at math, science and coding, and GPT-5, which can answer known scientific questions better than PhD students in the field and won Gold at the Maths Olympiad.8 Once AI gets close to being able to do AI research, we could see this kind of leap in under a year, starting from a point where the models are already around human level.

Early discussions concerned whether it could happen literally overnight (‘foom’), but today few people think that’s plausible. It still takes time to run experiments and do training runs. But it could unfold on a scale of months. And the process won’t stop there.

Hardware feedback loops

Today the number of AI chips produced is doubling roughly every year.9 If that trend continues, the computing power that could run 270 million AIs in one year will grow to be enough to run about 540 million the next. There would also be twice as much computing power available for AI training, so they’d become smarter too.

If each chip costs about $2 per hour to run, but can do the work of a human knowledge worker, those chips could generate $20 or even $200 an hour of revenue. Chip production would become one of the world’s biggest priorities, seeing not hundreds of billions, but trillions of dollars of investment. AI companies would direct the hundreds of millions of AI workers at their disposal to the task of accelerating chip production as much as possible. So it’s likely chip production would accelerate too.10

More chips would generate even more revenues, which would pay for even more chips, which would make AI even better. This is the chip hardware-driven feedback loop, and it has stronger evidence behind it than the algorithmic one:11

Each time the amount of computing power doubles, there is twice as much to run AI models (inference). Naively, twice as many instances means they can do twice as much work, so should earn (almost) twice as much revenue. On top of that, the amount of computational power available for training also increases two times.12 That means those models also get smarter and more efficient, which also makes them even more useful.

In fact, this seems to be what’s currently already happening. Each year, frontier AI companies increase the amount of computing power at their disposal by about 3x – 4x. But their revenues have been increasing 4x to 5x per year.13

Moreover, each time investment into chips has doubled, the amount of available computing power has increased much more than that. From 1971 and 2011, investment in semiconductors increased 18-times but the amount of computing power in a chip increased one million times due to innovation and economies of scale. The paper Are Ideas Getting Harder To Find shows that doubling investment into computer chips has led to a 5x increase in computing power.14

These two effects compound: each time AI companies double their revenue, they can reinvest in chips that will allow give them more than twice as much computing power next generation. Then each time computing power doubles, it can be used to run more than twice as many, better quality digital workers, who can earn more than twice as much revenue. (At least until other limits are hit, which I’ll discuss later.)

Whether it’s via the algorithmic or hardware feedback loop, we could quite quickly end up in world with many billions of AI workers that can be hired tens of cents per hour. It’s possible that these AIs quickly reach what’s been called artificial “superintelligence” (ASI): AI that’s more capable than humans at basically every cognitive task. This is no longer just an idea, but rather is the explicit goal of the leading AI companies who’ve raised hundreds of billions of dollars in pursuit of it.15

Superintelligence could mean AIs that are capable of much greater insights than humans. But it could also mean AIs that are about equally smart, but outstrip us due to other advantages. Picture the most capable human you know, then imagine they could crank up their processing speed to think sixty times more quickly – a minute for you would be like an hour to them. Now imagine they could make copies of themselves instantly, and that everything one copy learned could be shared with the others. Imagine a firm like Google but where the CEO can personally oversee every worker, and every worker is a copy of whoever is best at that role.

Whether we end up with superintelligence or a vast number of better-coordinated human-level digital workers, this process has been called the “intelligence explosion,” but it’s maybe more accurate to call it a “capabilities explosion,” because AI wouldn’t only improve in terms of narrow bookish intelligence, but also in creativity, coordination, charisma, common sense, and any other learnable ability.

Experts in the technology believe there’s a 40–60% chance the intelligence explosion argument is broadly correct, and a 10% chance AI becomes vastly more capable than humans within two years after AGI is created.16 Though this seems low to me.

2. The technological explosion

What would happen after an intelligence explosion has started? There are about 10 million scientists in the world today.17 If these hundreds of millions of AIs became as productive as human scientists, then the effective number of researchers would increase by 100-fold (and keep growing). Even though there are many other bottlenecks to science besides the number of scientists, this would almost certainly speed up the rate of technological progress. Forethought have also estimated we could see 100 years of technological progress in under ten, and maybe a lot more.18 We could call this the “technological explosion”.19

To get a sense of how wild this would be, imagine for a moment that everything discovered in the 20th century was instead discovered between 1900 and 1910. Quantum physics and DNA sequencing, computers and the internet, penicillin and genetic engineering, jet aircraft and space satellites would all happen within just two or three election cycles.

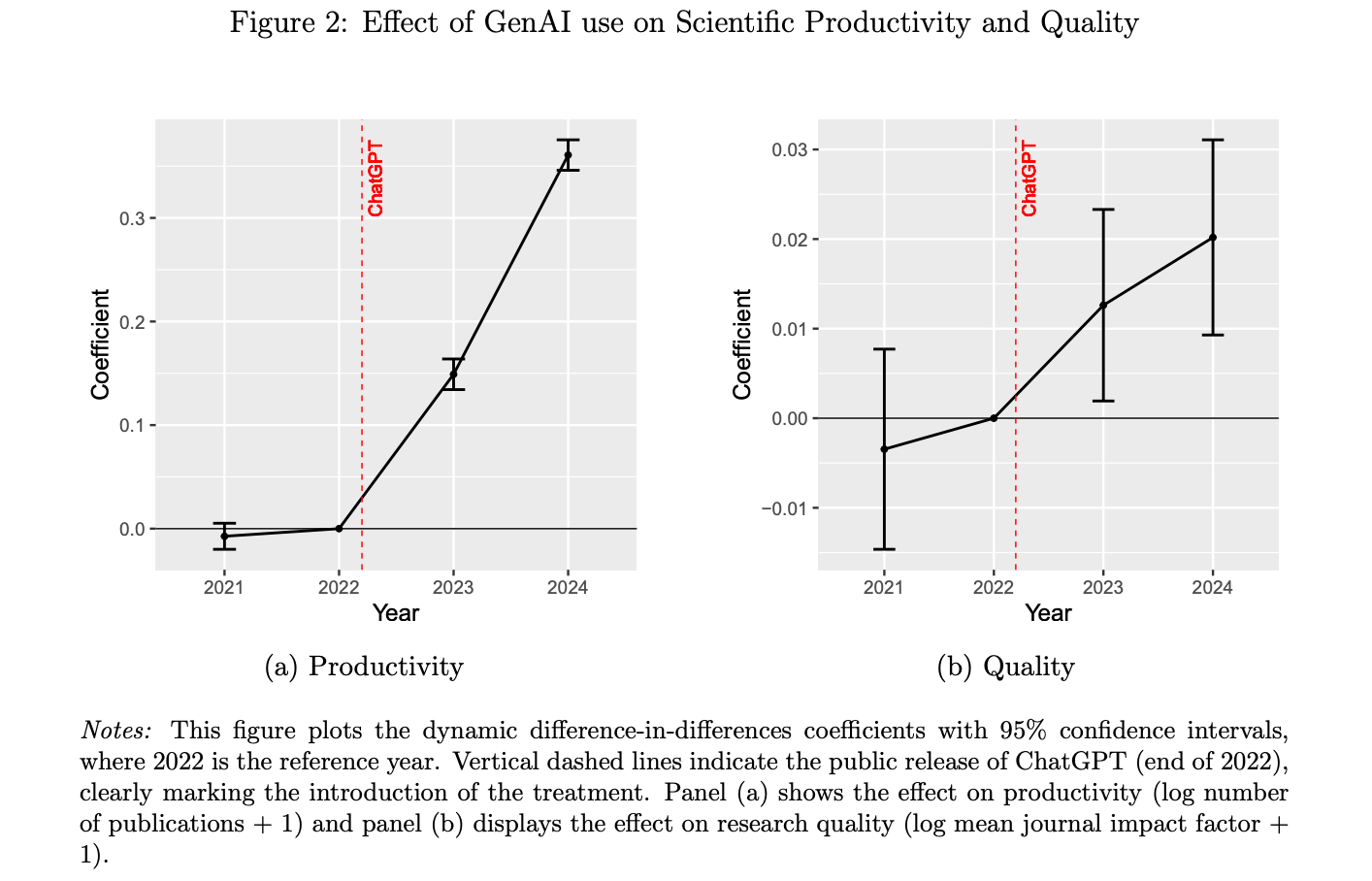

Initially this could look like specialist AI tools, like AlphaFold, which solved the protein folding problem and earned its creators the Nobel Prize. More recently, a paper found that scientists using AI were producing about 30% more papers in 2024 compared to similar scientists who weren’t, and these papers were if anything higher quality.20

Eventually, it looks like AI models that can answer questions humans don’t yet know how to answer, or run huge numbers of automated experiments, effectively doing work that would have taken hundreds of human scientists or been impossible before. The CEO of Anthropic sketched how this might look for biomedical research in his AI-optimism manifesto “Machines of Loving Grace”.

Much intellectual work, like maths or philosophy, could proceed virtually, so unfold very fast. However, what these digital scientists could do would quickly become limited by their inability to interact with the physical world. Robotics would then become the world’s most profitable activity. This leads us onto…

3. The industrial explosion

Robotic worker feedback loops

Soon after the outbreak of World War II, American car factories were converted to produce military planes. Today, car factories produce about 90 million cars per year,21 and if they were converted to produce robots, it’s possible they could produce 100 million to 1 billion human-sized robots per year.22

Without robots, the intelligence explosion fizzles out at the point where disembodied intelligence is no longer useful. Maybe everyone already has a 100 PhDs checking every tiny decision. The revenue an additional AI chip can earn would drop below the cost of producing one.

However, AI combined with advanced robotics can potentially do almost every economically important task, including building the factories, solar panels and chip fabs needed to produce more robotic workers.

This means a bunch of robotic workers can do some work and earn some money, then that can be used to construct more robotic workers. That larger group of robotic workers can then earn even more revenue, which can be used to construct even more robots, and so on. What effect would this have?

Epoch AI is one of the leading research groups at the intersection of AI and economics, and have created some of the only models that explore what a true human-level robotic worker would mean for the economy. They show, for instance, that if it becomes possible to produce a general purpose robot for under $10,000, and you plug that into a standard economic growth model, output would start to grow 30% per year.23 This has been called the “industrial explosion”.

It happens for the simple reason that if you have twice as many workers, and twice as many tools and factories, then they can produce about twice as many outputs (in terms of real goods and services rather than GDP). This is a widely accepted idea in economics with empirical support, called constant returns to scale.24

This doesn’t happen in the current economy, because if output doubles, the number of workers doesn’t increase, so output doesn’t rise very much. Giving the same number of workers a factory that’s twice as big doesn’t mean they can produce twice as much. But when it’s possible to simply build a new robotic worker, that constraint no longer applies. This leads to growth in output that is still exponential like today, but much faster.

If the AI workers can also contribute to innovation, then as the population of AIs grows, the amount of innovation they can do also increases, which means each AI worker gets more powerful technological tools, which increases their output even further (arguably this is a fourth ‘productivity’ feedback loop that results from the technological explosion). In this scenario, output accelerates over time, growing super-exponentially.25

While an algorithmic feedback loop would likely peter out quite fast as diminishing returns to algorithmic research are reached, the industrial explosion can keep accelerating until physical limits are reached. These could be very high.

As one illustration, Forethought argue that robot production would more likely be constrained by energy shortages than a lack of raw materials. If 5% of solar energy were used to run robots at around the efficiency of the human body, that would be enough to run a population of 100 trillion(!)26 at which point expansion into space would begin.

The speed of an industrial explosion is ultimately limited only by the minimum time it’s possible to build an entire production loop of solar panels, chip fabs and robots. No-one knows how fast that could ultimately be, but there are biological organisms, like fruit flies, that can replicate a brain and miniature ‘robot’ in about a week, so it could eventually become very fast.

Common counterarguments

It’s also possible there’s enough tasks robots remain unable (or are not allowed) to do that an industrial explosion can’t get started (despite the insanely large financial and military incentives to do so). Financial markets don’t currently seem to predict any increase in economic growth, and economists remain skeptical of the possibility.

But when most economists try to model the effects of AI, they implicitly assume it remains a complementary tool to human workers. If you model the effect of a robot that can actually substitute for human workers, it’s pretty hard not to get explosive growth. Most of their arguments against explosive growth are just arguments that sufficiently autonomous robotic workers won’t be possible, not that explosive growth won’t follow if they are.

A common response is that mass automation would make everyone unemployed which would crash demand. But the initial stages would produce a boom in wages. In addition, more than half of Americans have net worth over $100,000, and they would quickly become multimillionaires. Then about 25% of GDP is taxed, and most of that is redistributed as welfare. These forces would sustain demand even if employment drops.

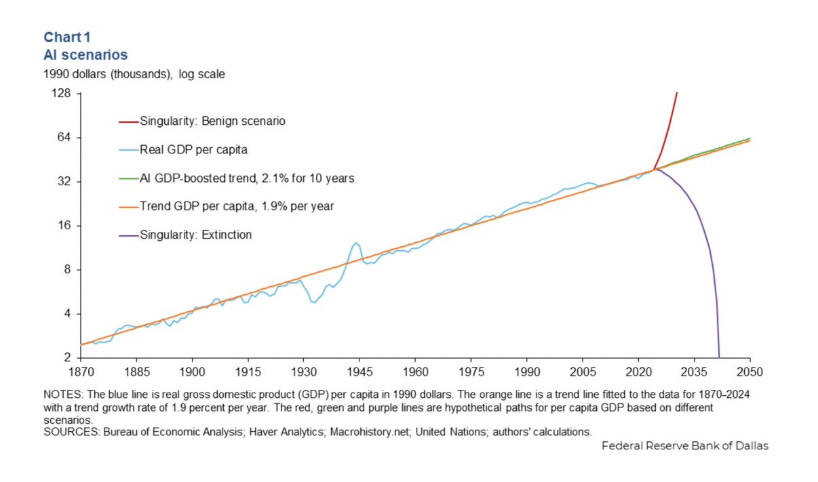

More and more economists are starting to take the possibility of explosive growth seriously, even if they haven’t truly internalised the implications, as in this this report on how “AI will boost living standards” by the Dallas FED:

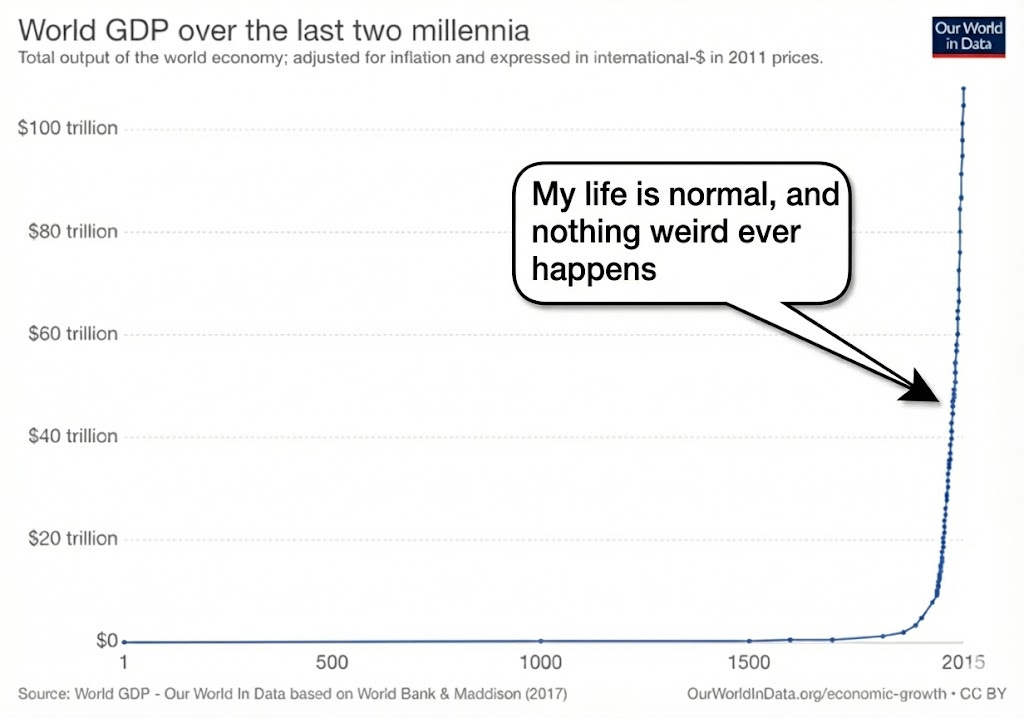

Keep in mind also that an economic acceleration has already been happening over the last few thousand years. Before the agricultural era, there was virtually no economic growth. After that, it increased to perhaps 0.1% per year. During the industrial revolution, growth accelerated again to over 1% per year.

The rate of growth has been steady the last 100 years, but that’s because the population stopped growing in line with the size of the economy. AI and robots would resume the old dynamic whereby more output leads to a larger ‘population’, and that dynamic leads to superexponential growth.

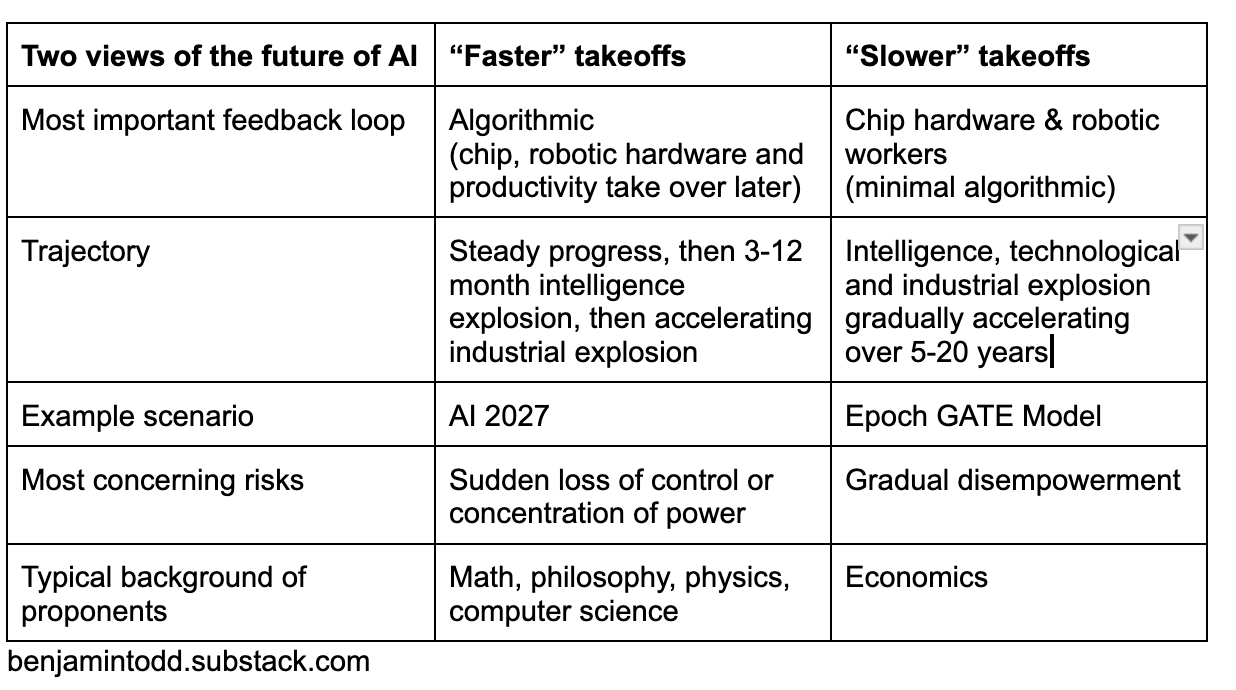

Two views of the future of AGI

It’s possible that AI won’t be able to carry out algorithmic research, scientific research or many ordinary jobs any time soon. If additional investments in computing power stop increasing AI capabilities, or revenues aren’t high enough, then AI capabilities will gradually plateau.27

Perhaps AI will end up extremely capable in some narrow dimensions, like mathematics and coding, but there will remain so much it can’t do that the economy carries on as before.28 This is what happens with most technologies even ‘revolutionary’ ones. Electric lights were a big deal, but once we all have them, we don’t buy ever more of them in a self-sustaining loop. The purpose of this article, however, is to explore what will happen if AI capabilities don’t plateau.

What happens is a mixture of everything I’ve covered above, but people who’ve thought about it a lot have tended to divide into two main camps:

The first camp is most concerned about the algorithmic feedback loop. Maybe AI remains a long way from being able to do most jobs, but it turns out to be especially good at one thing: coding and AI research. These are purely virtual tasks, with clearly measurable outcomes that match the current strengths of the models.

While daily life continues to look basically the same as before, somewhere in a datacentre, 10 million digital AI researchers are taking part in a self-sustaining algorithmic feedback loop. Less than a year later, there’s 300 million smarter-than-human AIs – a “country of geniuses in a datacentre”28 – now deployed to max out chip production, robotics production, scientific research, and then automation of the economy. These digital workers could drop into existing jobs, and so diffuse far faster than previous technologies.

This scenario is extremely important to prepare for, because it’s the most dramatic and dangerous. We could go from the normal world to one with superintelligent AIs in just a year or two. A single company could end up with 10x or 100x the intellectual firepower of the entire scientific community today.

This is the kind of scenario explored in Situational Awareness or AI 2027, which explores what would happen if an automated coder were created in 2027 . I don’t think an automated coder will be created in 2027, but it’s very possible the AI companies get close enough within the next ten years, and on balance, I think an algorithmic feedback loop is more likely than not (though I’m unsure how far it will go).

A scenario that seems quite likely to me now is one where AI progress continues, and perhaps gradually slows after 2028, as it becomes harder and harder to scale up computing power. AI capabilities remain very jagged and unable to do the long-horizon planning, strategy or continual learning that would make it autonomous. But it is useful enough to generate a lot of revenue and more scientific breakthroughs, which means investment continues to grow. Then at some point in the 2030s the final bottlenecks are overcome (or a new paradigm is created) and an algorithmic feedback loop starts.

Unlike AI 2027 there’s a longer gap between things starting to get obviously crazy, and a full intelligence explosion. This means society will have more time to prepare, but it also means it might start in a world full of much more intense conflict, and with much more robotic infrastructure already in place.

The second camp thinks an algorithmic feedback loop isn’t possible, but they still think the intelligence, technological and industrial explosions will happen. The difference is they’d need to be driven by the chip hardware, robotic worker and productivity feedback loops instead.

This is the kind of scenario explored in Epoch’s GATE model – the first attempt to make an integrated macroeconomic model of AI automation. It starts at the point where an AI is created that can do 10% of economically important tasks, and models how reinvestment into computer hardware could drive revenue and automation ever higher.

Given their default assumptions, within five years, GDP has doubled and growth has reached 20%, and from there continues to accelerate. After 15 years, GDP is 30-times larger, there’s 500 billion AI workers, and growth has reached 50% per year. Even if you add additional frictions, things still get pretty crazy pretty fast.

What’s clear is that — faster, slower, or somewhere in between — society isn’t remotely prepared for any of these scenarios.

As a result, we could see a dramatic expansion in wealth and technology, which would make it far easier to tackle many global problems. But it would also pose novel, and truly existential risks. Which are they? Read this.

The concept of recursive self-improvement in artificial intelligence dates back to the field’s founding figures. I. J. Good, who worked with Alan Turing at Bletchley Park, wrote in 1966:

“Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an “intelligence explosion,” and the intelligence of man would be left far behind.”

Good, Irving John. “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine”. Advances in Computers, vol. 6, 1966, pp. 31–88, https://incompleteideas.net/papers/Good65ultraintelligent.pdf.

In 1950, Turing wrote that “a machine undoubtedly can be its own subject matter. It may be used to help in making up its own programs, or to predict the effect of alterations in its own structure. By observing the results of its own behaviour it can modify its own programs so as to achieve some purpose more effectively.”

Turing, Alan M. “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”. Mind, vol. 59, no. 236, Oct. 1950, pp. 433–60, https://www.cs.ox.ac.uk/activities/ieg/e-library/sources/t_article.pdf↩

See a list of ways AI is being used to assist with AI research here:

Woodside, Thomas. “Examples of AI Improving AI”. Center for AI Safety, 2 Oct. 2023, https://ai-improving-ai.safe.ai/

Anthropic recently published a survey of how their own staff are using AI, and the results seem consistent with a 3-30% boost per worker, even accounting for the self-reports likely being an overestimate.

St Louis Fed finds that the average worker in ‘computer and math’ industries reports to be saving about 2.5% of their time with AI, but use of AI is far more intense within the AI companies themselves than within the average software company, so I’d expect that number is too low.

I’ve also informally polled experts in AI risk research, and most of them estimate the current degree of uplift for AI researchers is in the 3-30% range.

In fact, a lot of AI research might be easier to automate than many other jobs, because it’s a purely virtual task with clear metrics, there are no regulatory barriers, and it’s what people at the AI companies best understand how to do.

Epoch AI estimates that OpenAI in 2025 has enough computing power to run about 7 million “AI workers” with the abilities of GPT-5. There are other companies with a comparable amount of computing power, and Google has significantly more.

This number could increase going forward as available computational power is increasing around 2–4x per year, and because inference efficiency is increasing rapidly. At a fixed capability level, the number of models that can be run also often increases over 10x per year. But it could also decrease if future models are larger or require multimodal inputs. Overall I expect it to increase somewhat. Denain, Jean-Stanislas, et al. “How Many Digital Workers Could OpenAI Deploy?” Epoch AI, 3 Oct. 2025, https://epoch.ai/gradient-updates/how-many-digital-workers-could-openai-deploy.

This estimate is in line with previous estimates. For instance, Eth and Davidson estimate that OpenAI could run the equivalent of millions of human workers with the capabilities of its leading model at the time in the late 2020s.

“If you have enough computing power to train a frontier AI system today, then you have enough computing power to subsequently run probably hundreds of thousands of copies of this system (with each copy producing about ten words per second, if we’re talking about LLMs). But this number is only increasing as AI systems are becoming larger. Within a few years, it’ll likely be the case that if you can train a frontier AI system, you’ll be able to then run many millions of copies of the system at once.”

Eth, Daniel, and Tom Davidson. “Will AI R&D Automation Cause a Software Intelligence Explosion?” Forethought, 26 Mar. 2025, https://www.forethought.org/research/will-ai-r-and-d-automation-cause-a-software-intelligence-explosion#a-toy-model-to-demonstrate-the-dynamics-of-a-software-intelligence-explosion

Davidson, Tom, and Tom Houlden. “How Quick and Big Would a Software Intelligence Explosion Be?” Forethought, 4 Aug. 2025, https://www.forethought.org/research/how-quick-and-big-would-a-software-intelligence-explosion-be

Epoch AI did a survey of estimates of the improvements in training efficiency, and found a rate of about 3x per year.

Training and inference efficiency are not the same, but many experts expect them to move similarly.

Inference efficiency as measured with cost per token has actually increased much faster than 3x per year, though some of this could be due to reducing profit margins.

Epoch AI reports GPQA Diamond scores of 31–36% for GPT-4, which is little better than random guessing (25%), and 85–86% for GPT-5, well above the 70% level achieved by humans with a PhD in the field and access to Google .

“GPQA Diamond.” Epoch AI, https://epoch.ai/benchmarks/gpqa-diamond/

Nvidia’s datacentre revenues have more than doubled each year for the last three years (and accounts for the majority of spending on AI chips; the second biggest source being Google’s investment into TPUs, which have also grown rapidly). In addition, the chips have become over 30% more efficient per dollar each year, so in terms of computational power, production is increasing over 2.6x per year. Each chip lasts for 4-6 years, but this rapid rate of growth means that about half of the computational power comes from the chips produced in the last year, and that total available computational power is roughly doubling each year.

NVIDIA Corporation. Form 10-K: For the Fiscal Year Ended January 26, 2025. 2025, https://s201.q4cdn.com/141608511/files/doc_financials/2025/q4/177440d5-3b32-4185-8cc8-95500a9dc783.pdf

You, Josh, and David Owen. “Leading AI Companies Have Hundreds of Thousands of Cutting-Edge AI Chips.” Epoch AI, 2024, https://epoch.ai/data-insights/computing-capacity.

Rahman, Robi. “Performance per Dollar Improves Around 30% Each Year.” Epoch AI, 2024, https://epoch.ai/data-insights/price-performance-hardware

Though this would need to be weighed against it becoming harder and harder to scale up chip production as the quantities involved get larger. For example, while AI data centres use about 1% of electricity today, if that continues to double every year, then eventually pretty soon you’d need to add more than 100% of current power generation every year in new capacity.

This argument for increasing returns is discussed in more detail in:

Train once, deploy many: AI and increasing returns, by Ege Erdil and Tamay Besiroglu, March 2025, Epoch AI

https://epoch.ai/blog/train-once-deploy-many-ai-and-increasing-returns

There are some countervailing forces, notably diminishing returns to the utility of additional AI, and competition between frontier labs, which could drive down revenues, but at least in recent history, these haven’t been strong enough to offset the factors that cause increasing returns.

On diminishing returns, this could be because AI is a small fraction of the economy, so we’re a long way from ‘using up’ all the ways it could be applied. This effect mostly goes away if AI + robotics become able to replicate the entire production process, but there could be an intermediate phase where AI becomes bottlenecked by other inputs, such as physical manipulation.

On competition, there’s a relatively small number of frontier companies, and progress has been very fast. This enables these small number of leaders to offer a significantly better product than commoditised trailing edge models, giving them the ability to charge large revenues. This will likely remain the case as long as rapid AI progress continues.

Today roughly half of AI chips are used for inference and half are used for training. That means if you triple the total stock of chips, the amount of available for both inference and training increases 3x

We don’t have great estimates of computing spending and revenue at the frontier AI companies, but Epoch AI has pieced together available data to make the following estimates, which are roughly consistent with trends of 3-5x per year in recent years.

“AI Companies.” Epoch AI, 2 Dec. 2025, https://epoch.ai/data/ai-companies/

The striking fact, shown in Figure 4, is that research effort has risen by a factor of 18 since 1971.” Figure 4 also shows that transistor count increased about 1 million times between 1971 and 2011.

In table 7, they show beta for semiconductor TFP growth is 0.4. This means the exponent of the production function is 1/0.4 = 2.5. That means if you double investment, then TFP has increased (2)^2.5 = 5.6.

Bloom, Nicholas, Charles I. Jones, John Van Reenen, and Michael Webb. “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?” American Economic Review 110 (4): 1104–44, Apr. 2020, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20180338/, preprint PDF

For instance, OpenAI has announced their internal target is to have an automated AI researcher by 2028, with the goal of creating superintelligence soon after. This specific timeline is probably too optimistic, but it reveals what they’re aiming towards.

Bellan, Rebecca. “Sam Altman Says OpenAI Will Have a ‘Legitimate AI Researcher’ by 2028.” TechCrunch, 28 Oct. 2025, https://techcrunch.com/2025/10/28/sam-altman-says-openai-will-have-a-legitimate-ai-researcher-by-2028/.

Altman, Sam. “The Gentle Singularity.” Sam Altman’s Blog, 10 June 2025, https://blog.samaltman.com/the-gentle-singularity. Epoch data shows that by October 1st 2025, the combined funding for OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI reached roughly $94 billion, representing about a twofold increase from October 2024. In the near future, OpenAI alone has committed to spending around 1 trillion dollars, mostly on deals for additional compute infrastructure.

Epoch AI. Data on AI Companies. 4 Nov. 2025, https://epoch.ai/data/ai-companies.

McMahon, Bryan. “The AI Ouroboros.” The American Prospect, 15 Oct. 2025, https://prospect.org/2025/10/15/2025-10-15-nvidia-openai-ai-oracle-chips/

Grace, Katja, et al. “Thousands of AI Authors on the Future of AI”. arXiv, 5 Jan. 2024, https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.02843↩

According to UNESCO’s most recent comprehensive data, there were 8.854 million full-time equivalent (FTE) researchers worldwide in 2018, representing a 13.7% increase from 2014. Given the observed growth rate of around 3.4% per year between 2014 and 2018, and assuming continued growth at a similar pace, the global researcher population would be expected to approach or exceed 10 million by 2025. “Statistics and Resources”. UNESCO Science Report 2021: The Race Against Time for Smarter Development, UNESCO, 2021, https://unesco.org/reports/science/2021/en/statistics

MacAskill, William, and Fin Moorhouse. “Preparing for the Intelligence Explosion”. Forethought, 11 Mar. 2025, https://www.forethought.org/research/preparing-for-the-intelligence-explosion

Though the acceleration wouldn’t be confined to hard technology, but rather all forms of intellectual and scientific progress, especially those that can mainly be done virtually. This would include things like the invention of new political philosophies. Just as the 20th century had to navigate new ideologies like communism and fascism over 100 years, we might need to navigate radical new alternatives in just ten

Filimonovic, Dragan, Christian Rutzer, and Conny Wunsch. “Can GenAI improve academic performance? Evidence from the social and behavioral sciences.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.02408 (2025). link

“List of Countries by Motor Vehicle Production”. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://archive.ph/cB7fU. (Archived link retrieved 10-Sep-2025.)

I’ve written about this on substack, though also see a more detailed analysis in Forethought’s piece on the industrial explosion.

Erdil, Ege, and Tamay Besiroglu. “Explosive Growth from AI Automation: A Review of the Arguments”. arXiv.Org, 15 July 2024, https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.11690

Constant returns to scale is widely assumed in economics and consistent with empirical evidence. If anything, empirical evidence supports increasing returns to scale – in which twice as many workers and capital assets can produce more than twice as much. This happens due to increased innovation and economies of scale

Ege Erdil and Tamay Besiroglu demonstrate this in their paper “Explosive growth from AI automation: A review of the arguments”, link.

In brief, the idea is that each time the population and capital stock doubles, that enables you to double output due to constant returns to scale. In addition, the number of innovators also doubles, which increases the rate of innovation. This also makes the workers more productive, so they produce even more than twice as much next generation. This then enables the population to increase by an even greater amount next time, and so on.

Davidson, Tom, and Rose Hadshar. “The Industrial Explosion”. Forethought, 21 May 2025, https://www.forethought.org/research/the-industrial-explosion

If you object there wouldn’t be enough land area for these robots, please consider: https://waitbutwhy.com/2015/03/7-3-billion-people-one-building.html

Unsticking that plateau might require waiting for many decades of chip research or economic growth to make training AI affordable enough to continue. For instance, chips become 30-40% cheaper each year, so if you wait for ten years, the cost of training AI decreases 20 fold. With 3% GDP growth, if you wait 25 years, the economy is twice as big, which means makes training AI twice as affordable.

This phrase comes from Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, describing the capabilities of what he calls “powerful AI”. Amodei, Dario. “Machines of Loving Grace”. Dario Amodei, Oct. 2024, https://darioamodei.com/essay/machines-of-loving-grace

Could there be a robotics bottleneck? Like a situation where disembodied intelligence is extremely advanced but where the relatively slow progress of robotics (either occuring naturally or artificially made slow through regulation) limits the ability of AI to take over the most embodied kinds of human jobs, like plumbing, piano playing, or charisma-based jobs (e.g. politics)?

It seems to me that a lot of embodied knowledge is not currently stored in an AI readable format like a textbook. So to reach AI doing 100% of human tasks we would first need a human-like or superhuman robot (which seems like a huge task requiring a lot of cooperation between human experts and requires quite a lot of material procurement which, again, AI can't get on its own) and then we would need to train it in order to reach proficiency in that discipline. Two steps that in my opinion could be much more easily slowed down with regulation than software progress... Perhaps an avenue to consider for AI safety?

Separately, I was wondering how much effort is being done right now in producing machines or technologies that detect data-centre activity, even when hidden deep underground. Such a technology might be useful if we need to urgently pull the plug on AI development whilst it's still disembodied...

https://graywade.substack.com/p/19-toys-for-tots?r=1mvbk6